Best practice handling to reduce flesh bruising

This article appears in the Summer 2018 edition of Talking Avocados (Volume 28 No 4).

Best practice handling to reduce flesh bruising

By Melinda Perkins, Muhammad Mazhar, Daryl Joyce, Noel Ainsworth, Lindy Coates and Peter Hofman

Improving the quality of avocado fruit purchased by consumers is a primary goal of the Australian avocado industry. Flesh bruising is among the most common avocado quality defects encountered at retail. It can cause substantial consumer dissatisfaction. In our last Talking Avocados article (Winter 2017), we discussed production of more robust fruit through careful pre-harvest management and harvesting as a farm-based approach to reducing flesh bruising at retail. Here we discuss the post-harvest side of the issue in terms of: what can be done to limit exposure of the fruit to damage events likely to cause bruising; and, how much is ‘too much’ damage? We briefly review the current state of knowledge and propose best practice recommendations towards reducing flesh bruising at retail.

When does bruising occur?

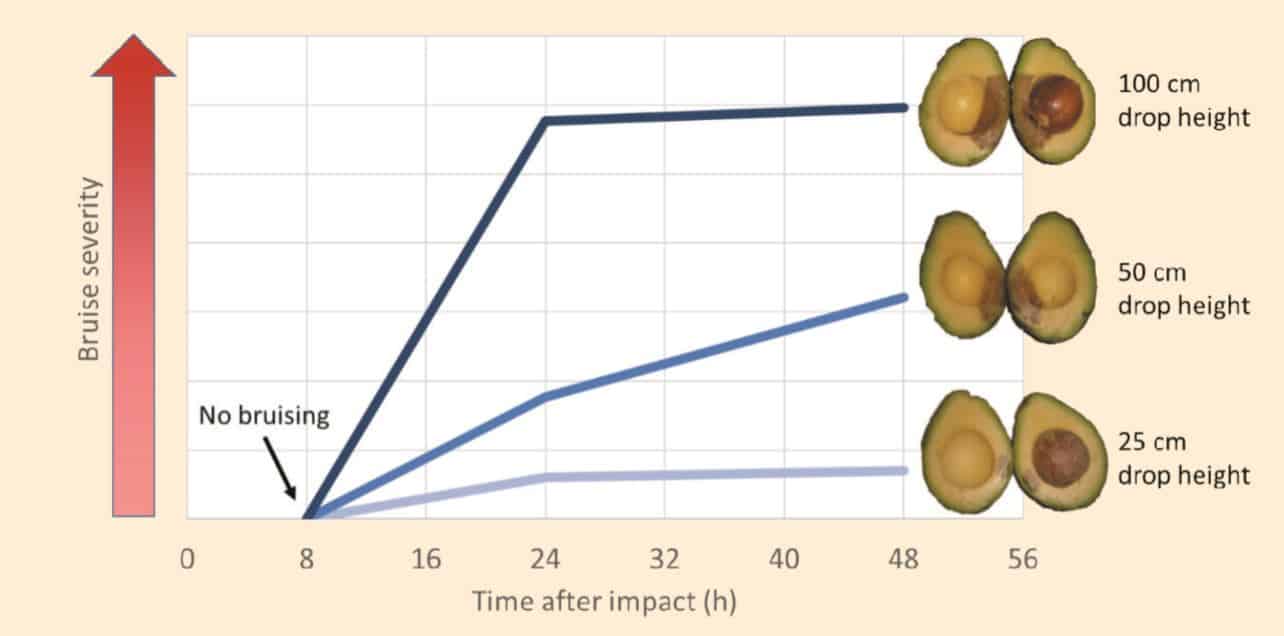

Flesh bruising is most evident in avocado fruit at the retail and consumer stages in the supply chain. Studies conducted within the past five years suggest that bruising affects around one in every three Hass fruit sampled from retail displays1, 2. In contrast, bruising has been reported to occur in less than one in every 10 fruit sampled between harvest and packhouse3 and from ripener and distribution centre1. In investigating events that lead to flesh bruising, we note that injured avocado flesh takes about 24 hours to develop the visible resultant bruise1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Relative bruise severity development over time in ‘firm-ripe’ stage cv. Hass avocados subjected to impacts from various drop heights. Photos show visible flesh bruising 48 hours after impact

What events cause the most bruising?

Greater degrees of bruising at later stages in the supply chain are the result of two factors. Firstly, fruit becomes more susceptible to bruising as they ripen and soften1, 4-7. Secondly, fruit are increasingly squeezed by retail staff, shoppers and consumers when being ‘tested’ for ripeness6 (Figure 2). In a survey of Australian avocado consumers, 97% squeezed avocado fruit when assessing ripeness8. Moreover, shoppers have been observed to handle three times more avocados than they actually purchase6. Thus, most fruit on retail display have likely been squeezed multiple times.

Figure 2: Squeezing of avocado fruit on retail display to ‘test’ for ripeness (courtesy Sha Liao)

These squeezing or compression events generally cause enough damage to express as bruising of the fruit flesh. It has been found that shoppers typically apply compression forces ranging from three to 30 Newtons (N) to firm-ripe avocado fruit when assessing ripeness6. For context, a ‘slight’ thumb compression of 10N applied to a firm-ripe fruit causes visible bruising within 48 hours at 20°C. Single squeezes by shoppers produced varying degrees of bruising in every fruit assessed and bruising was more severe than in non-handled fruit6. Extensive bruising occurred in fruit subjected to multiple handling; that is, fruit handled once by each of 20 different shoppers6 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Hass avocado fruit exhibit extensive flesh bruising in response to multiple handling by shoppers

Post-purchase handling of fruit by consumers also contributes to total bruising. Bruise-free fruit provided to consumers at retail check-out and subjected to their ‘normal’ handling practices for two days developed greater incidence (ie frequency) and severity (ie degree) of bruising than non-handled fruit6.

In addition to squeezing or compression, striking or impact damage at all stages of the supply chain can adversely affect final fruit quality. For unripe Hass avocados at the hard green mature stage, controlled impact from a drop height of 100cm caused tissue injury. However, flesh bruising did not show up when the fruit finally ripened9. Nevertheless, our research suggests that a drop height of 30cm for hard green mature fruit can trigger body rot development upon ripening, while a drop height of 15cm does not (unpublished data). These findings of increased decay highlight the need for careful handling of fruit from harvesting onwards through the whole supply chain. Hence, keeping drop heights below 15cm for hard green mature fruit will probably reduce the incidence and severity of body rots at retail and consumer stages.

As fruit ripen, the drop or impact height at which bruising develops decreases. At the ‘softening’ stage, a 10cm drop height caused substantial bruising of >3mL flesh bruise volume. Bruising was relatively negligible at <1mL bruise volume for drop heights ≤5cm (Ledger, unpublished data). For ‘firm-ripe’ fruit, drop heights of 2-3cm were sufficient to cause bruising5, 7.

Temperature can affect avocado bruise expression. For cv. Hass, damage events result in substantially less bruise volume if fruit temperature is maintained at 5°C post-injury. Impact from 25cm did not result in bruise expression in ‘firm-ripe’ fruit subsequently held at 5°C1. However, the same impact caused visible bruising in at least nine of 10 fruit held at either 15 or 25°C1. Maintaining relatively low fruit temperature is also important for suppressing postharvest disease expression10, 11.

How can bruising be avoided?

Education and training

Retail staff, shoppers and consumers all need to be aware of their crucial roles in maintaining avocado fruit quality. In this regard, education is critically important in reinforcing correct handling techniques which minimise flesh bruising. Most consumers do not link their ‘bad avocado experience’ with excessive handling. Only 42% agreed with a statement that “bad avocados have been handled or touched too much”8. Importantly, shoppers should be encouraged to limit their squeezing of fruit. Moreover, fruit selected for purchase should be carefully packed with chilled grocery items and promptly taken home. Once ripe (ie, soft), avocado fruit can then be kept in the refrigerator for use within three days. On the other hand, encouraging consumers to purchase unripe fruit may reduce their risk of encountering bruising. However, many consumers seek ‘ripe-and-ready’ fruit. Also, consumers generally lack the confidence to ripen fruit at home8. In this respect, ‘how-to’ guides can be provided.

Workers at all stages in the supply chain from harvest to retail need to be instructed and reminded to maintain cv. Hass fruit at 5°C wherever possible, except during ripening. Drop heights ≥15cm must be avoided for hard fruit. For softening fruit, drop heights should be kept below 10cm. Retail staff should be educated and reminded to handle fruit from firm-ripe stage onwards ‘like eggs’, without dropping and/or careless squeezing.

Retail display

Managing retail displays to promote rapid stock turnover and lessen handling events can reduce handling of individual fruit. Small volume displays might logically be assumed to result in rapid stock rotation. However, data from the USA suggests that small volume displays are a barrier to purchase12. Large displays, on the other hand, were reported to promote sales by inspiring shopper confidence that the avocados are fresh12 and by capturing the attention of impulse buyers13. Around one-third of impulse buyers in the USA indicated that an eye-catching display influenced their decision to purchase avocados13. The display size required to minimise bruising is likely to vary with retail store type and location and also shopper demographics. It is problematic to make recommendations on retail display size until its effects on fruit quality have been fully researched.

Posters, signage and leaflets add visual impact to displays and also present opportunity to provide point-of-sale advice (Figure 4). Most consumers considered that posters at the point of purchase are a preferred source of information on avocado selection, storage, ripening and usage8. Arranging the display into different ripeness categories has been shown to reduce fruit handling by shoppers (Hort Innovation project AV15011, unpublished data).

Figure 4: Prominent point-of-sale poster provides information to shoppers on avocado selection (courtesy Sha Liao)

Packaging

Selling avocados in pre-pack formats, such as plastic-wrapped trays, netting bags or clamshell punnets (Figure 5) may potentially reduce bruising by limiting individual fruit handling by consumers. However, careful studies are warranted to quantify the effect of packaging on avocado bruising at retail. Moreover, consumers in general prefer to purchase loose avocados, including because they find it difficult to judge quality and ripeness of packaged avocados12, 13. In Australia, 83% of avocado consumers indicated that their purchases for the previous month were comprised solely of loose avocados14. Nonetheless, pre-packaged avocados are gaining popularity in overseas markets. In the USA, the pre-packaged segment of the retail avocado market has risen sharply in the past two years to now comprise around a third of total sales volume15. Small avocados marketed as ‘mini’, ’baby’ or ‘cocktail’ fruit are increasingly available in Europe16-18 and North America19, and tend to be sold in pre-packaged formats.

Figure 5: Avocado ‘pre-pack’ options available in Australian supermarkets: (a) flowpacked rigid plastic tray, (b) netting bag and (c) clamshell rigid plastic punnet

Technology

Development of in-store decision aid tools (DAT) to enable non-bruising assessment of fruit firmness by retail staff and shoppers is a relatively novel approach to reduce flesh bruising in avocado fruit. A range of sensor technologies have been tested with a view to non-destructively assessing avocado firmness. They include acoustic resonance, laser Doppler vibrometry, low mass impact sensors, micro-deformation sensors, near infra-red spectroscopy, optical-based tactile sensors and ultrasound. However, none are currently being used in retail environments. Obstacles to commercial use include cost, operator skill and /or maintenance and calibration. A prototype DAT based on a force-sensing resistor placed between the thumb and the fruit was recently developed and tested by us for in-store use. In-store surveys found it was favourably received by shoppers. The device was rated as “helpful” or “very helpful” for assessing avocado firmness by 97% of survey participants (unpublished data). However, a cost-effective retail-ready DAT is still some development and commercialisation ‘time’ away from adoption.

Recommendations

On the basis of past and recent studies, the following post-harvest practices are recommended to reduce flesh bruising and /or body rots in avocado:

- keep drop heights below 15cm for hard green mature fruit

- keep drop heights below 10cm for softening fruit

- handle fruit carefully without dropping or excessive squeezing from firm-ripe stage onwards

- hold fruit at 5°C where possible (except during ripening).

Practices which are likely to limit avocado bruising, but for which strong supporting evidence is still lacking, include:

- train retail staff in appropriate handling techniques

- arrange retail displays into ripeness categories

- provide point of sale information on fruit selection for ripeness

- provide consumers with ‘pre-pack’ options

- inform consumers of appropriate in-home handling and storage techniques.

The above measures have already been implemented by the Australian avocado industry in varying combinations and extents. Presumably, widespread uniform adoption requires more compelling evidence of effectiveness in lessening flesh bruising. In this regard, three concurrent co-ordinated Hort Innovation avocado supply chain quality improvement projects are working towards this goal through investigating techniques to reduce bruising (AV15009) and quantifying benefits of appropriate cool chain management (AV15010) and retail displays (AV15011).

Acknowledgement

The Supply chain quality improvement – Technologies and practices to reduce bruising project (AV15009) is being conducted by the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries in collaboration with The University of Queensland and Avocados Australia Ltd. The project is funded by Hort Innovation using the avocado levy and contributions from the Australian Government.

References

1. Joyce, D.C., M.S. Mazhar, and P.J. Hofman (2015). Reducing flesh bruising and skin spotting in ‘Hass’ avocado. Final report AV10019. Horticulture Australia Limited, Sydney, Australia.

2. Tyas, J. (2016). Avocado industry fruit quality benchmarking. Final report AV11015. Horticulture Innovation Australia, Sydney.

3. Hofman, P.J. (2002). Bruising of ‘Hass’ avocado from harvest to the packhouse. Final report AV02015. Horticulture Australia Limited, Sydney.

4. Arpaia, M.L., F.G. Mitchell, P.M. Katz, and G. Mayer (1987). Susceptibility of avocado fruit to mechanical damage as influenced by variety, maturity and stage of ripeness. South African Avocado Growers’ Association Yearbook 10, 149-151.

5. Baryeh, E.A. (2000). Strength properties of avocado pear. Journal of Agricultural Engineering Research 76, 389-397.

6. Joyce, D.C., M.S. Mazhar, and P.J. Hofman (2015). Understanding and managing avocado flesh bruising. Final report AV12009. Horticulture Australia Limited, Sydney, Australia.

7. Ledger, S.N. and L.R. Barker (1995). Black avocados – the inside story, p. 71-77. In: The Way Ahead. Proceedings of the Australian Avocado Growers’ Federation Conference, Freemantle, 30 April – 3 May.

8. Jones, T. (2014). Project Avocado Education QN. Final report AV12035. Horticulture Australia Limited, Sydney.

9. Mazhar, M., D. Joyce, G. Cowin, I. Brereton, P. Hofman, R. Collins, and M. Gupta (2015). Non-destructive 1H-MRI assessment of flesh bruising in avocado (Persea americana M.) cv. Hass. Postharvest Biology and Technology 100, 33-40.

10. Everett, K.R. (2003). The effect of low temperatures on Colletotrichum acutatum and Colletotrichum gloeosporioides causing body rots of avocados in New Zealand. Australasian Plant Pathology 32, 441-448.

11. Hopkirk, G., A. White, D. Beever, and S. Forbes (1994). Influence of postharvest temperatures and the rate of fruit ripening on internal postharvest rots and disorders of New Zealand ‘Hass’ avocado fruit. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science 22, 305-311.

12. Hass Avocado Board (2013). Shopper Path to Purchase Study. http://www.hassavocadoboard.com/sites/all/themes/hab/pdf/HAB-Path-to-Purchase-Study.pdf. Accessed 28 April 2017.

13. Hass Avocado Board (2015). Shopper Path to Purchase Study. http://www.hassavocadoboard.com/sites/default/files/hab-ptp-quant-full-reportv1-usda-approved.pdf. Accessed 28 April 2017.

14. Allen, A. (2007). Australian avocado consumer research. AV04015 final report. Horticulture Australia Ltd, Sydney.

15. Hass Avocado Board (2017). Retail volume and price data. http://www.hassavocadoboard.com/retail/volume-and-price-data. Accessed 10 December 2017.

16. Butler, S. (2017). M&S selling stoneless avocado that could cut out risk of injuries. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/dec/07/marks-and-spencer-stoneless-avocado Posted 8 December 2017. Accessed 11 December 2017.

17. Butler, S. (2017). Tesco to sell tiny avocados in response to fruit’s global shortage. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/aug/18/tesco-to-sell-tiny-avocados-for-just-a-few-weeks Posted 19 August 2017. Accessed 11 December 2017.

18. Van Gastel, E. (2017). Mini avocados simply more festive during the holidays. Fresh Plaza. http://www.freshplaza.com/article/185958/Mini-avocados-simply-more-festive-during-the-holidays Posted 12 April 2017. Accessed 11 December 2017.

19. McMurrain, R. (2017). Introduction of Tiny Tim’s mini avocado product line. Fresh Plaza. http://www.freshplaza.com/article/184726/Introduction-of-Tiny-Tims-mini-avocado-product-line Posted 11 December 2017. Accessed 11 December 2017.

Date Published: 31/01/2018