By Noel Ainsworth, Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

The uniformity of ripening is of interest to retailers to make it simpler for consumers to select and purchase fruit.

This can minimise bruising caused by handling during selection, which is responsible for half of the damage that consumers see in avocado.

Uneven ripening on the other hand reduces sales and increases time required by store staff to top up displays. Food waste is more likely due to some fruit getting overripe in the retail display.

Practices such as picker training, monitoring of dry matter by growers and ripening practices contribute to improved uniformity of maturity. There are several papers reporting on controlled experiments that identify a link between fruit maturity and speed of ripening. The AV18000 avocado supply chain feedback project reviewed the maturity of fruit and whether it is affecting the uniformity of ripening. Results from the 811 fruit examined across all five districts in year two of the project, found that the link between dry matter and ripeness was weak.

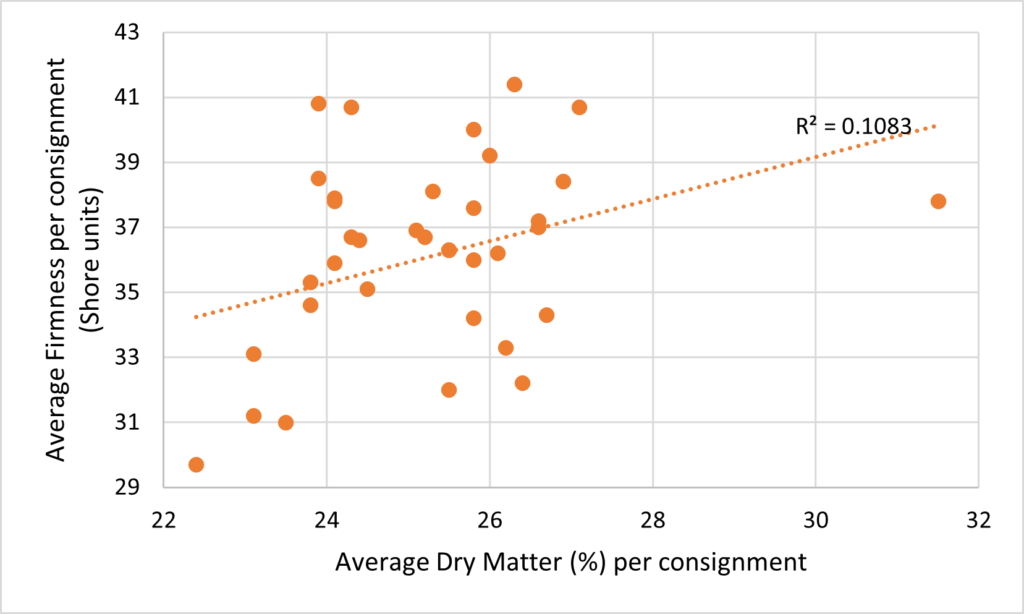

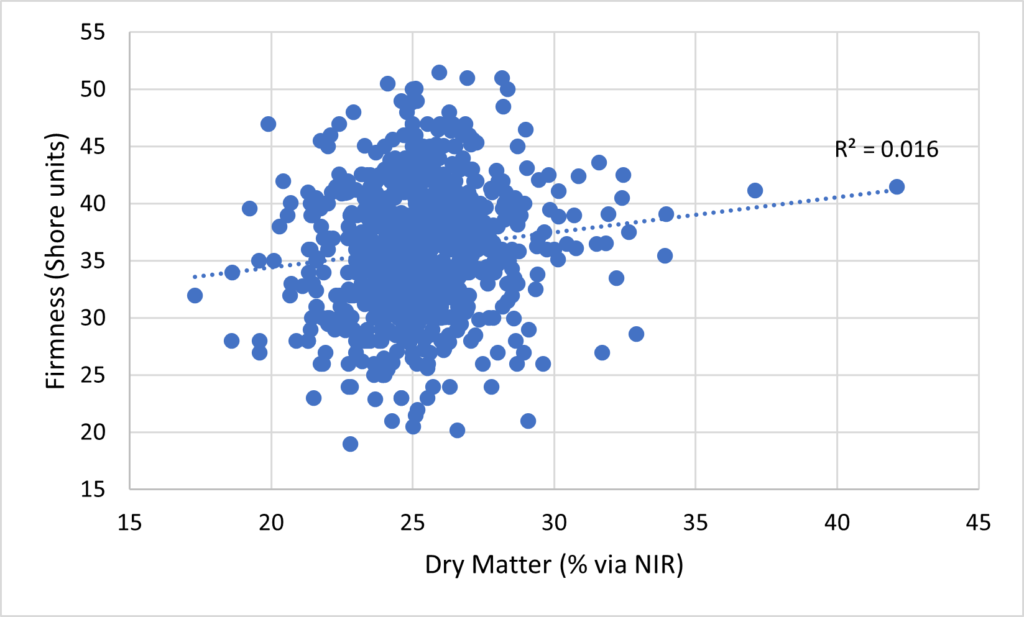

As a check, the dry matter of fruit was monitored through the year and by production district. There was no underlying trend that might affect the investigation. The relationship between dry matter and fruit firmness at assessment was then examined as an average per tray sample (Figure 1) and again on an individual fruit level (Figure 2). In both instances we suspected that low dry matter would result in higher fruit firmness and vice versa, but this was not the case. This is something that we can review as year three data comes to hand.

Figure 1. Average dry matter versus average firmness per tray of ~20 fruit

Figure 2. Dry matter versus fruit firmness for individual fruit samples

While we have confidence in the dry matter accuracy using the Felix NIR device and similarly the firmness reading using the Turoni durometer, there are other factors that may be masking a clearer relationship including:

- dry matter may be too focused in the mid-range (23-27% dry matter) with insufficient data either lower or higher than that range

- sampling fruit from a broad range of farms and production districts is likely to include a broad range of nutrition/rootstocks

- other robustness factors contributing to fruit firmness.

One implication of this lack of a link is that there is no current justification for retailers to ask growers to segregate fruit by maturity (using dry matter) in an effort to improve the uniformity of ripening on the retail shelf.

In the BPR

Throughout this article, we have linked to useful resources in the BPR. If you don’t have BPR access, click here to apply. The BPR is available for Australian-based members of the avocado industry.

More information

Noel Ainsworth, Principal Supply Chain Horticulturist, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, Mobile 0409 003 909, Email noel.ainsworth@daf.qld.gov.au

The AV18000 project has been funded by Hort Innovation, using the Hort Innovation avocado industry research and development levy, co-investment from the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries, the Western Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development and contributions from the Australian Government. Hort Innovation is the grower-owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture. Key project delivery partners also include Avocados Australia Ltd and Rudge Produce Systems.